NASA GSFC

NASA’s TESS Spots Record-Breaking Stellar Triplets (News Release - October 2)

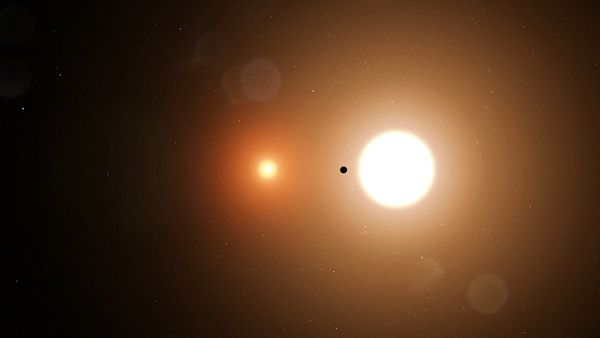

Professional and amateur astronomers teamed up with artificial intelligence to find an unmatched stellar trio called TIC 290061484, thanks to cosmic “strobe lights” captured by NASA’s TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite).

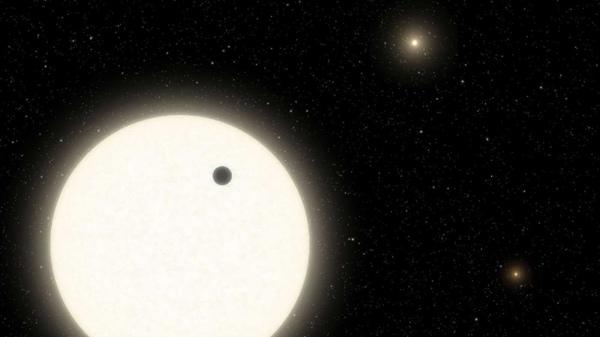

The system contains a set of twin stars orbiting each other every 1.8 days, and a third star that circles the pair in just 25 days. The discovery smashes the record for shortest outer orbital period for this type of system, set in 1956, which had a third star orbiting an inner pair in 33 days.

“Thanks to the compact, edge-on configuration of the system, we can measure the orbits, masses, sizes and temperatures of its stars,” said Veselin Kostov, a research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California. “And we can study how the system formed and predict how it may evolve.”

A paper, led by Kostov, describing the results was published in The Astrophysical Journal on October 2.

Flickers in starlight helped reveal the tight trio, which is located in the constellation Cygnus. The system happens to be almost flat from our perspective. This means that the stars cross right in front of, or eclipse, each other as they orbit.

When that happens, the nearer star blocks some of the farther star’s light.

Using machine learning, scientists filtered through enormous sets of starlight data from TESS to identify patterns of dimming that reveal eclipses. Then, a small team of citizen scientists filtered further, relying on years of experience and informal training to find particularly interesting cases.

These amateur astronomers, who are co-authors on the new study, met as participants in an online citizen science project called Planet Hunters, which was active from 2010 to 2013. The volunteers later teamed up with professional astronomers to create a new collaboration called the Visual Survey Group, which has been active for over a decade.

“We’re mainly looking for signatures of compact multi-star systems, unusual pulsating stars in binary systems, and weird objects,” said Saul Rappaport, an emeritus professor of physics at MIT in Cambridge. Rappaport co-authored the paper and has helped lead the Visual Survey Group for more than a decade. “It’s exciting to identify a system like this because they’re rarely found, but they may be more common than current tallies suggest.”

Many more likely speckle our galaxy, waiting to be discovered.

Partly because the stars in the newfound system orbit in nearly the same plane, scientists say that it’s likely very stable despite their tight configuration (the trio’s orbits fit within a smaller area than Mercury’s orbit around the Sun). Each star’s gravity doesn’t perturb the others too much, like they could if their orbits were tilted in different directions.

But while their orbits will likely remain stable for millions of years, “no one lives here,” Rappaport said. “We think the stars formed together from the same growth process, which would have disrupted planets from forming very closely around any of the stars.” The exception could be a distant planet orbiting the three stars as if they were one.

As the inner stars age, they will expand and ultimately merge, triggering a supernova explosion in around 20 to 40 million years.

In the meantime, astronomers are hunting for triple stars with even shorter orbits. That’s hard to do with current technology, but a new tool is on the way.

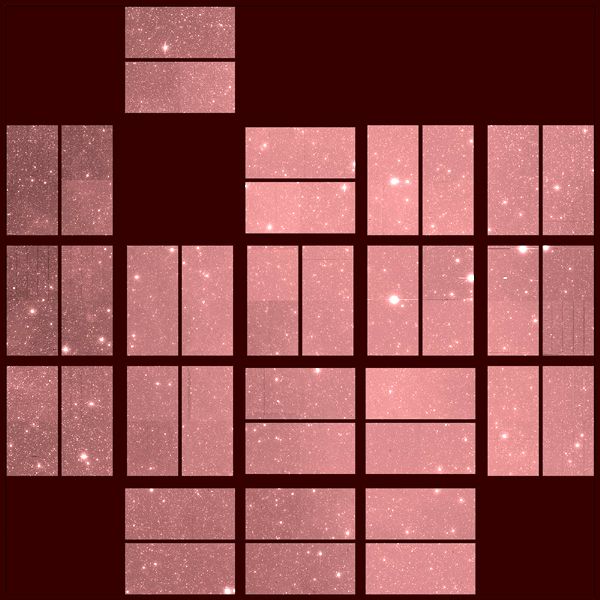

Images from NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will be much more detailed than TESS’s. The same area of the sky covered by a single TESS pixel will fit more than 36,000 Roman pixels. And while TESS took a wide, shallow look at the entire sky, Roman will pierce deep into the heart of our galaxy where stars crowd together, providing a core sample rather than skimming the whole surface.

“We don’t know much about a lot of the stars in the center of the galaxy except for the brightest ones,” said Brian Powell, a co-author and data scientist at Goddard. “Roman’s high-resolution view will help us measure light from stars that usually blur together, providing the best look yet at the nature of star systems in our galaxy.”

And since Roman will monitor light from hundreds of millions of stars as part of one of its main surveys, it will help astronomers find more triple star systems in which all the stars eclipse each other.

“We’re curious why we haven’t found star systems like these with even shorter outer orbital periods,” said Powell. “Roman should help us find them and bring us closer to figuring out what their limits might be.”

Roman could also find eclipsing stars bound together in even larger groups — half a dozen, or perhaps even more all orbiting each other like bees buzzing around a hive.

“Before scientists discovered triply eclipsing triple star systems, we didn’t expect them to be out there,” said co-author Tamás Borkovits, a senior research fellow at the Baja Observatory of The University of Szeged in Hungary. “But once we found them, we thought, well why not? Roman, too, may reveal never-before-seen categories of systems and objects that will surprise astronomers.”

Source: NASA.Gov

****

NASA GSFC